|

|

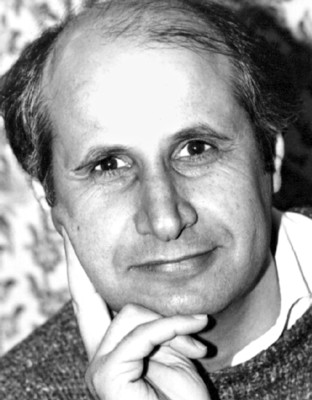

In his stories Alafenisch gives a multicolored, multi-faceted (facettenreich) and vivid picture of tribal Bedouin culture. His stories are an ethnographic document of the Bedouins. In an interview, he said that he felt that his duty was to preserve one part of his cultural heritage: storytelling. His books are the only written document that the Bedouins of the Negev Desert possess. In the stories he writes of traditional customs and habits and also of actual problems of the Bedouins, who still live in Israel. He heard the stories mainly from his mother. Maybe this is the reason why he often tells stories of marriages decided upon by the fathers and arranged by the mothers and celebrated in big festivities (three days long). In all his stories the ship of the desert - the camel - is not missing. It is the symbol of richness and prestige. The dowry for a bride is measured not by gold and silver but by camels. The higher the number of camels that a groom has to bring for a dowry the more important is the bride. His first book Der Weihrauchhändler tells stories of adventure, love and mysterious journeys interwoven with many amusing anecdotes. The story telling is a central pillar of his writings. I like to illustrate this with one example: A guest visits the tribe. Before he can express the purpose of his visit (of course packaged as a story) a competition erupts among the members of the tribe, about who will host the guest. What do you think: Who wins the bet? Of course, the one who tells the most beautiful story. In his latest book Amira im Brautzelt, Amira is a beautiful princess of the desert whom all young men would like to marry. So she has to choose among a big number of admirers. After examining their qualities and interviewing a few of them, she can’t decide. There are three young men whom she would like to marry. Her grandmother says this is not possible. You are a woman and you are allowed to have only one husband at a time. The grandmother gives her a tip about how to choose the best out of the three. Of course, she should marry the one who tells the most beautiful story. In Die acht Frauen des Großvaters, he describes the life of the women in the Negev desert. In eight episodes, his mother gives him an overview of the tribal traditions and customs of the Bedouins. She tells stories of solidarity among women and at the same time shows that the women practically have limited rights. ”If your husband treats you badly we will bring him to the woman Kadi. Your flesh belongs to him, but your soul belongs to your tribe.“ This is what the father tells Fatima after he arranged her marriage without her consent. This technique of story telling and embedding a story in a story in a story can be endless. This is not a new technique. I am sure each of you know the Tales of One Thousand and One Night where this technique saved the life of Sheherezade and she gave birth to three children before the king decided that he would keep her because she was so smart. Salim Alafenisch and the others revived this technique and reintroduced it to the German audience with new current topics. The Bedouins don’t know any boundaries. They move around where they find grass and water. They settle down as long as they have enough to feed their cattle and themselves. Maybe this is one of the reasons why his stories have no boundaries, they are woven into each other and that is difficult to tell when one starts and the other ends. With this technique Salim Alafenisch would like to show the senselessness of boundaries. His stories can be seen as a kind of healing for the Zeitgeist (Heilung für den Zeitgeist) and the better understanding of different peoples and cultures. Klaus Farin wrote in The Zeit in 1989: “The stories of Salim Alafenisch are fluid, they never reach a single point. The journey is the goal, the joy of narration (and of listening), and not the art of concluding a tale determines the unique suspense of these stories. Bedouins don’t die of heart attacks.“ In his book, Das Kamel mit dem Nasenring, (The camel with the nose ring) the oldest of his tribe says, „There are three types of storytellers: Some are like a water skin whose content last for only a few days. Others are like wells, that have enough water for months. Finally, there are storytellers like fountains that never run dry.“ Salim Alafenisch is such inexhaustible font. Books

by Salim Alafenisch

|

|||||||

He

He